Drugs that instantly relieve anxiety can feel like a godsend, but using the pills long-term may come with serious consequences.

When Rachel Ziegler was 22, her doctor prescribed 0.5 mg of Xanax once a day to treat generalized anxiety and panic attacks. “I don’t recall ever discussing a potential stopping point,” says Ziegler, who works as a chemistry-lab technician at the University of Illinois, “but I do remember asking her if I would become addicted.” Ziegler says her doctor minimized the risk, telling her, “Oh, you’ll be okay. You’d have to take it like three times a day for three months to get addicted.” But after about three months, the psychiatrist wrote her a new prescription, then another, until before she knew it she’d been using Xanax for six years.

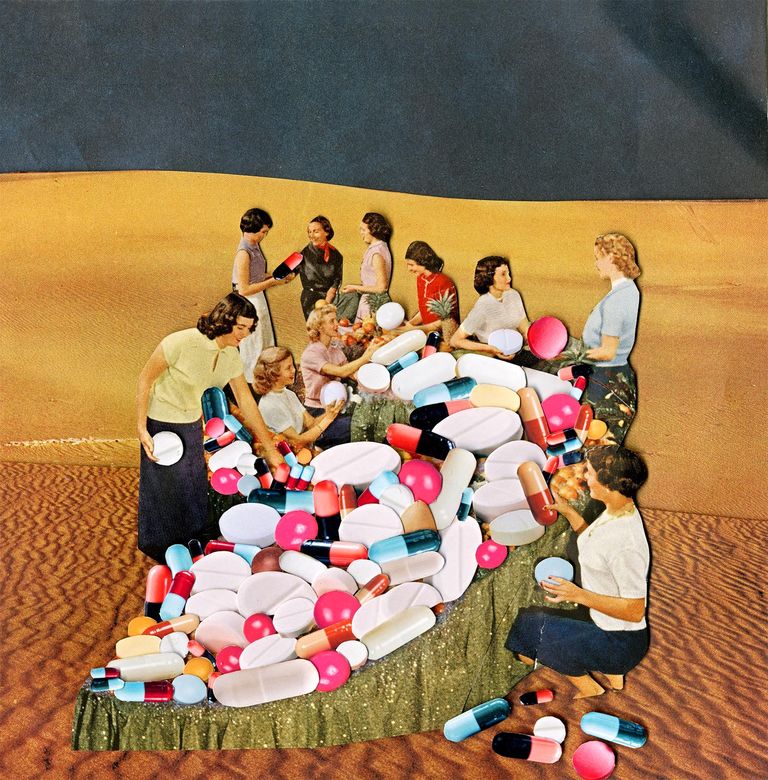

Xanax is the most well-known brand in the class of drugs known as benzodiazepines; other popular brands include Klonopin and Ativan. “Benzos,” as the drugs are culturally known, are sedatives for the age of anxiety—popular preflight fear quellers and an instant blunter for life’s sharp edges: breakups, deadlines, funerals. They’re readily prescribed and passed around friend groups like brunch recommendations, and they’ve gotten shout-outs in everything from rap songs to New York Times columns. Benzo-praising memes say it loud and proud: Our brains need help, and these drugs are the salve. But we don’t talk enough about the consequences of use over time and withdrawal or how women are disproportionately impacted.

Women are twice as likely as men to have an anxiety disorder and thus also twice as likely to be prescribed benzodiazepines, according to a 2019 report in JAMA Network Open. Between 1996 and 2013, benzodiazepine prescriptions increased by 67 percent, from 8.1 million to 13.5 million, according to a 2016 study in the American Journal of Public Health. The increase in use and misuse has led to a concerning spike in deaths: The overdose mortality rate involving benzodiazepines for women between the ages of 30 and 64 increased by 830 percent between 1999 and 2017, according to a January 2019 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Often, women don’t know what they’re getting into. “Most people taking psychiatric drugs these days do not get an adequate explanation about the nature of the medication,” says George Dawson, M.D., a Minnesota-based addiction psychiatrist. That was the case for Summer Schley, a 26-year-old waitress in Valley View, Pennsylvania, who was prescribed Klonopin to help her sleep when she was 18. “I didn’t know what the term tolerance meant,” she says. “I never did pills or even drank alcohol, so I was completely unaware of what I was given.”

Drug packaging states physiological dependence can occur even when they’re taken as prescribed, but it doesn’t explain dependence is widespread among users who take the drugs for longer than two to four weeks, according to a 2018 article in the Journal of Clinical Medicine. And many do: Between 2005 and 2015, the number of people using benzos for six or more months increased by 50 percent, according to the JAMA report. “Anyone who uses these medications long-term is going to experience tolerance and withdrawal,” says Wilson Compton, M.D., the deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Common withdrawal symptoms include increased anxiety and heart rate, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood instability, dizziness, and cognitive difficulties. Joseph Garbely, D.O., medical director at Caron Treatment Centers, a Pennsylvania-based nonprofit dedicated to addiction and behavioral health-care treatment, education, and prevention, says benzo withdrawal is “the worst we deal with.” Jen Chouinard, who was prescribed Klonopin for PTSD, experienced a stabbing pain in her eyes, elbows, and feet, ringing in her ears, insomnia, stiff joints, and trouble concentrating when she went off the drugs. She also experienced rapid weight loss, dropping about 30 pounds. “People were like, ‘You look fabulous,’” says Chouinard, 33, a graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, “and I’m like, ‘Oh, I’m recovering from a drug addiction I didn’t know I had.’”

The best way out of this burgeoning crisis is a simple one: “We should really look at limiting the number of patients on chronic benzodiazepines,” says Stephen Delisi, M.D., of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, a national nonprofit addiction treatment provider. Dr. Compton agrees. “Part of the problem in our health-care system is that doctors spend 10 or 11 minutes with each patient. That’s not a good way to treat anxiety,” he says. “There’s a tendency to want to use medication for everything.” Other methods, like therapy, take longer to work but may be better in the long run. “Often the solutions are outside of the pill bottle—developing healthy coping strategies and dealing with life on life’s terms,” Dr. Garbely says.

Like many users, Ziegler developed a tolerance, taking up to 4 mg to get the same effect she did at 0.5 mg. “I had to keep taking more to get the anxiety relief that I needed so badly,” she says. Eventually, no amount seemed to be enough. In 2017, she spent a weekend “withdrawing in agony in my parents’ bed” when she was supposed to be at a wedding. “That’s when I finally came to terms with the fact that a drug had me completely under its thumb,” she says. “I was enslaved, and it was 100 percent terrifying.”

It took Ziegler about four months to taper off the drugs, a period marked by panic attacks, her body temperature oscillating between sweating and shivering, and what is known as “benzo rage,” which she describes as the “adult version of a toddler tantrum.” The last pill she took was in August 2017. “Benzodiazepines are extremely appealing because they work too well, too fast, and Americans are all about the quick fix,” says Ziegler, now 29. “But it’s pretty clear how we are paying the price.”

Reporting for this story was supported with a grant from the Scattergood Foundation.

This article originally appeared in the July issue of Marie Claire.